Rich and powerful people are prone to buying properties in the world’s most attractive places, whether that be the south of France, London or the Hamptons. Here, Christopher Benedict looks at one such property hot spot. He tells the fascinating story of King Zog I of Albania and how he purchased a mansion that he never visited in Long Island.

King Zog I of Albania.

The Gold Coast

The handful of hamlets and villages which comprise the Hamptons are collectively associated with Long Island’s go-to getaway spot, second home, or den of iniquity for contemporary celebrities. An all-inclusive VIP playground with a guest list reading like a who’s who of the well to do and the ne’er do wells. Faces familiar from movie screens and television sets, concert stages and the rear flaps of dustjackets. Personalities whose images with accompanying tales of achievement and debauchery alike are routinely spread throughout the pages of Vogue and Variety, Rolling Stone and Sports Illustrated, Fortune and Time.

The Hamptons are a relatively recent phenomenon and not at all relevant to the not too distant past when Long Island’s North Shore was the place to be and be seen (or not be seen, depending upon one’s desire for privacy and seclusion) for those who could afford such ostentatious status symbols as the mansions and sprawling estates built on what came to be known as the Gold Coast between just before the birth of the 20th century with its financial windfall created by the Industrial Revolution and the sobering death knell for the inebriated obliviousness of the Jazz Age (which turned blissfully blind eyes away from the horrific aftershocks of the First World War and flaunted their ill-gotten alcoholic party favors in the absurd face of the Volstead Act) sounded by Black Tuesday and the Great Depression.

Among the original occupants of these opulent, custom-built dwellings were luminous names such as William Vanderbilt, Alfred DuPont, J.P. Morgan, the Guggenheims, Lewis Tiffany, Frank Woolworth, William Robertson Coe, Otto Hermann Kahn, Henry Clay Frick, and John S. Phillips. Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay served as Theodore Roosevelt’s permanent domicile and ‘Summer White House’ while president. Oscar Hammerstein, W.C. Fields, Ring Lardner, Eugene O’Neill, Groucho and Chico Marx, not to mention their father and mother Sam and Minnie, all maintained addresses up and down the Long Island Sound for varying lengths of time and frequent visitors like Charlie Chaplin, Ethel Barrymore, Dorothy Parker, Herbert Bayard Swope, and Winston Churchill, to name but a few, came and went as they pleased.

The Gold Coast is most famous for its fictional depiction in The Great Gatsby, authored of course by short-term Great Neck denizen F. Scott Fitzgerald, who lived with Zelda on Long Island from October 1922 through April 1924and based the novel’s East Egg and West Egg on Port Washington’s Sands Point and Kings Point of the Great Neck peninsula respectively. Lands’ End, the manor many consider to have been Fitzgerald’s inspiration behind Daisy Buchanan’s home in Gatsby, was demolished in 2011, the property sold off for a five-unit sub-division. In fact, it is estimated that fewer than 400 of the approximately 1,200 mansions constructed from the 1890s to the 1930s remain standing, with some functioning today as national landmarks, historic sites, state parks, public gardens, and museums.

It is the dilapidated ruins of a massive structure once known as Knollwood in the Incorporated Village of Muttontown, however, and one of its intended residents in particular that concern us now.

Bloody Inauguration

Ahmet Zogu was born to a family of feudal landowners in their Burjaget Castle on October 8, 1859 in the Muslim province of Mati which had established an independence of sorts from its Christian neighbors eight years prior. Albania remained, at the time, under the thumb of the Ottoman Empire and young Ahmet was sent off to begin his studies in Constantinople, an academic endeavor which lasted for all of three years. Indeed, Zogu would live out his entire existence as a functional illiterate. His friend and future foreign diplomat Chartin Sarachi alleged in his unpublished memoirs that “Zog never learned Albanian grammar and…is unable to write a line in the Albanian language. He can write in the old Turkish alphabet, but indeed that very poorly.” Sarachi contends that Zogu had only ever read two or three books, and each of them biographies of Napoleon. Which itself speaks volumes.

Unlettered though he was, Ahmet would not allow this minor nuisance to thwart his ambition and patriotic fanaticism. At the age of sixteen, Zogu succeeded his deceased father as the Mati Governor and would add his signature to the Albanian Declaration of Independence in 1912. After having volunteered for service in the Great War on the side of Austria-Hungary, Ahmet would return home to a country fallen to disorder amidst a revolving parliamentary door of provisional figureheads, all of which Zogu served in some capacity or other.

From out of this chaos Ahmet ultimately emerged as Prime Minister and initiated several progressive if controversial measures such as converting expansive graveyards into public parks, liberating Muslim women from religious and social restrictions, outlawing polygamy, and drawing a firm line between religion and state. Shortly after being shot at by a student representing a radical group of young Albanian intellectuals who plainly saw tyranny dressed as democracy (one of a supposed 55 assassination attempts, as Albanian legend tells it), Zogu was forced into Yugoslavian exile in early 1924. Backed by a group of paid mercenaries 5,000 strong, he fought his way back across the Albanian border and reached the capital of Tirana on December 24 following two weeks of intense battle and much spilled blood. Ahmet almost immediately proclaimed himself President and made his designation official by virtue of a perfunctory election thrown together the following January. Thus did Zogu become not only Albania’s inaugural President but also the first Muslim sovereign of a European nation.

Chartin Sarachi remarked in his unfinished autobiography that Zogu “liked flattery and expected godlike veneration.” Those who failed to comply with these lofty wishes or in any way opposed his autonomy met with lengthy prison sentences or more decidedly grisly fates, prompting the European press to refer to Zog as “Ivan the Terrible of the Balkans.”

The Bizarre King

In the wake of his expulsion for criticizing “the fanatical, cross-bred, cringing, corrupt, face-grinding Beys and Moslems”, Albanian newspaper correspondent J. Swire wrote of Zogu in 1933 that “the alarming thing is that this very able man, the ruler of a very able people, is still so insecurely seated on a rickety throne.” Swire went on to suggest, “His death alone would be enough to provoke the break-up of the army, an explosion among the clans, intervention by land and sea and, possibly, a major war.” The root cause of this diagnosis lay in the fact that the country’s financial situation was not only devoid of equity but wildly lacking in accountability.

Zogu treated the extremely finite resources within Albania’s Treasury Department as a bottomless cookie jar from which he helped himself annually to more than twice his self-allotted £35,000 salary. He cut quite the ostentatious figure in an all-white ensemble of military tunic, feathered Cossack cap, gloves, pants, and patent leather shoes and his paramour Francy, a Viennese cabaret dancer with whom Ahmet became acquainted in Belgrade during his pre-presidential banishment, wore gowns produced by the finest Parisian dressmakers complimented by scores of jewels which, as Chartin Sarachi surmised, would have won the envy of Cleopatra.

When this malfeasance threatened to unravel into a national economic crisis, Zogu first sought relief from Russia’s ambassador in Vienna who refused to take the matter to Moscow much less any further than the consulate itself. With no Communist assistance forthcoming from the Soviet front, Ahmet turned his attention to Fascist Rome which proved much more receptive to Zogu’s entreaties. Having knowingly bought into the lie with ulterior motives already in mind, Benito Mussolini personally approved a £200,000 loan to help stave off what he was informed to be an imminent revolution. There was more than a scarce element of truth behind Zogu’s ruse, surrounded as he was not only by a discontented general population but by sycophants, illiterates, and traitors which Ahmet proudly yet contemptuously referred to as “my circus.”

The creation of an Albanian National Bank, established and kept solvent by international handouts and headquartered in Rome, was a laughable attempt at legitimacy and necessitated the signing of a formal alliance with Italy in 1927. What followed was the coronation of Zog I, King of the Albanians, in what could only have been an eerie procession. The monarch rode in an open-top automobile flanked by armed cavalry, traveling into Tirana past houses all adorned with Italian-made Albanian flags, inside of which the occupants were ordered to remain. The purpose of this was to keep the streets clear, eliminating any risk of assassination.

The Puppet Defies Its Master

If Zog was initially thought of as an easy mark who would exist contentedly and be manipulated effortlessly beneath the boot of Italy, Il Duce had another guess coming, particularly when the Balkan King brazenly rejected four of the seven demands included in a 1933 ultimatum drafted by Mussolini. The disputed points of contention called for “the dismissal of all Albanian high officials not of Italian origin, the removal of English officers commanding the police and their replacement by Italians, the reopening of Catholic schools recently closed by the government, and the replacement of the French school at Kortcha by an Italian school.”

Zog ran further afoul of Mussolini by subsequently entering into a commercial agreement with Yugoslavia as well as initiating diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. However, growing financial instability and a resulting small-scale rebellion in the city of Fier in 1935 would force Zog to relent to Mussolini’s ultimatum in order to guarantee the continual flow of money into Albania from Rome. Zog additionally sought to curry favor with his benefactor by publicly protesting the sanctions imposed upon Italy by the League of Nations as a penalty for its annexation of Ethiopia.

Ironically, it would be another annexation order issued by Mussolini – in 1939 against Albania – which would finally cause the two vainglorious dictators to come to loggerheads. Zog’s denial of Italy as Albania’s military protectorate would be his final act of defiance. Mussolini’s vengeful response arrived in the form of a naval bombardment from the Adriatic Sea which cleared the way for a boots-on-the-ground invasion over the Easter weekend. While the Albanian crown transferred to the head of Italy’s Vittorio Emanuel III, Zog escaped to Greece with his beautiful Hungarian bride Geraldine Apponyi and their infant son, Crown Prince Leka. From there, they re-routed to London where the royal family took sanctuary within the luxurious confines of the Ritz Hotel.

Knollwood

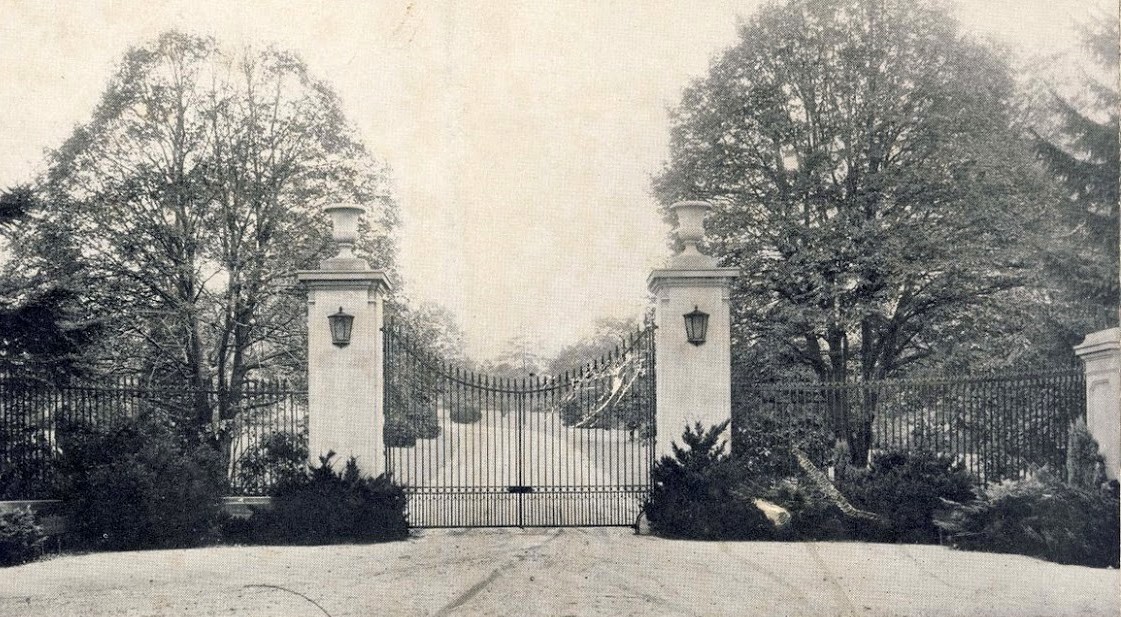

The famed Manhattan architectural firm of Hiss and Weeks drafted plans for the immense 60-room stone mansion which was constructed sometime between 1906 and 1920 as the centerpiece of Westbrook Farms, a 260-acre estate in Nassau County on Long Island intended for Charles Hudson who amassed his fortune through dealings on Wall Street as well as in the burgeoning steel industry.

With the purpose of utilizing Knollwood as a by-proxy Albanian kingdom, the exiled Zog purchased the estate in 1951 for a reported amount of $102,800, which today would equate to slightly less than a million dollars. Pillagers and vandals, fueled by speculation that Zog had completed the transaction by means of rubies and diamonds and already had hidden for him within the mansion by low-level Albanian functionaries his money and multitudinous treasures, looted and destroyed beyond repair the vacant premises.

Never having laid eyes or set foot upon the property, Zog sold it four years later and the Town of Oyster Bay declared the unsafe structure condemned and had it all but leveled to the ground in 1959. Accessible – albeit difficult to find – from hiking trails winding through the present-day Muttontown Preserve, the ruins of Knollwood are still today a popular destination for scavengers and curiosity-seekers who may not even necessarily be privy to the story of the obscure Albanian king who very nearly lived there.

And, so, what of Zog? Rather than Long Island, he and his family relocated to Paris where he died in 1961 and was buried in the Thiais Cemetery. In 2012, the Albanian government – including Zog’s grandson Leka, a political advisor to President Bujar Nashani – commemorated the centennial of the nation’s independence from the Ottoman Empire by having Ahmet Zogu exhumed and repatriated to Tirana.

Committed to a specially built mausoleum, Zog’s remains have fortunately received far more reverential treatment than those of the Gold Coast’s ransacked and bulldozed mansion.

Did you find this article fascinating? If so, tell the world. Tweet about it, share it, or like it by clicking on one of the buttons below.