Ben Parten takes us back to the 1900 World’s Fair and considers how W.E.B. Du Bois made attempts to overcome the Color Line and continued prejudice against African Americans through a breakthrough exhibition.

As the world turned its back on the nineteenth century and entered the twentieth, civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois assessed the social state of American society looking forward. In his famous book The Souls of Black Folk, he prophetically claimed, “For the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” In the latter half of the nineteenth century, Du Bois emerged as the intellectual voice of the race uplift movement, which sought to advance the social status of African Americans. Prior to his “color line” statement, Du Bois foresaw challenges approaching the black community and attempted to redirect the perceptions of African Americans on the world’s biggest stage: the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. Though primarily thought of as an exposition to showcase industrial and technological feats, Du Bois saw the World’s Fair as an arena where “the problem of the color line” could be denigrated by expressing the intellectual acumen and social progress of African Americans. If Du Bois and his team could effectively demonstrate to their European peers that the African American community was a thriving and active component of American society, it would be a step in the direction of racial tolerance at home and abroad.

Though Du Bois is conventionally identified with the Exhibit of American Negroes, the exhibit was initially organized by Thomas Calloway. After petitioning then President William McKinley for the necessary funds to conduct the project, he enlisted Du Bois and Daniel Murray – an assistant at the Library of Congress – to gather the appropriate materials. From these collected materials, Du Bois and Murray hoped to convey four different aspects of the African American community: their history, their present state, their education, and their literature. Accordingly, they assembled a large collection of patents from African American inventors and a bibliography of over 1,400 pamphlets and books written by African American writers. Most notable of these writers was the popular poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar. The group even constructed charts that mapped out the demographic status of African Americans within America and in comparison to Europe. Du Bois specifically points out in “The American Negro at Paris” that “there are nearly half as many Negroes in the United States as Spaniards in Spain” and illiteracy of African American children is “less than that of Russia and only equal to that of Hungary.”

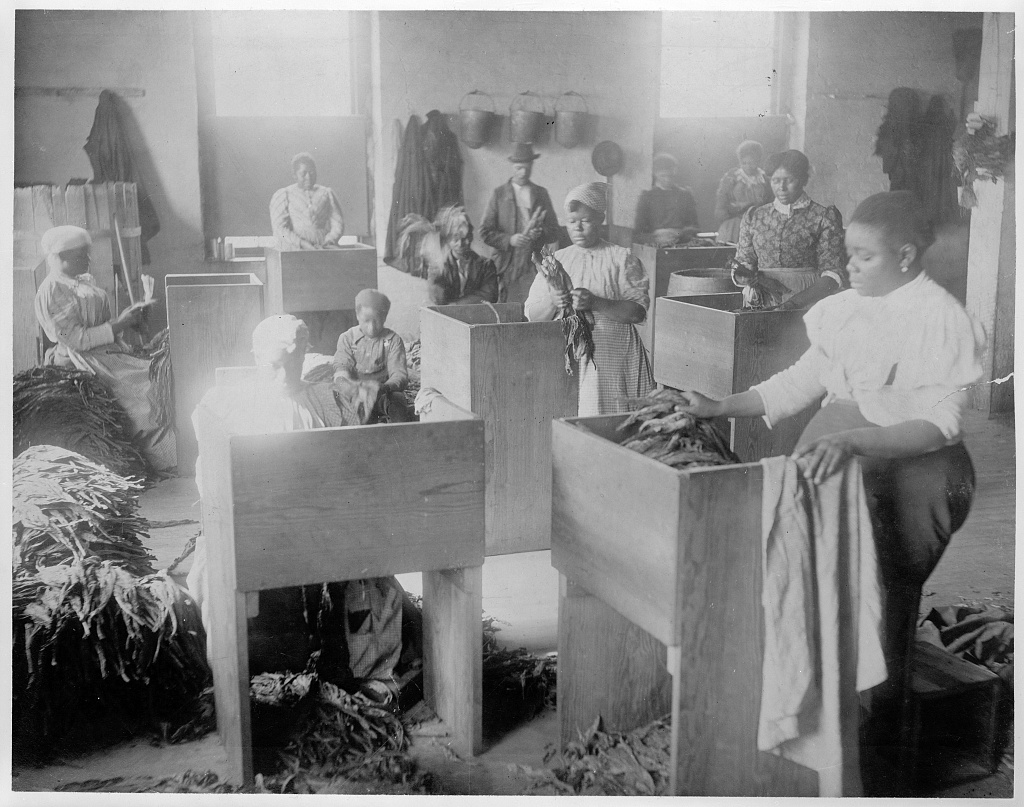

Yet, the most intriguing component of the exhibit was its compilation of photographs. Du Bois and Murray compiled over five hundred photographs highlighting the social progress of African Americans since emancipation. In order to highlight social advancement, these pictures often portrayed families, clubs, or single individuals dressed in nice clothes and sporting stylish accessories equal to those of whites. The pictures also conveyed the importance African Americans placed on education. Photos of whole graduating classes at the major African American colleges like Fisk and Howard were taken along with photos of younger students attending grammar school. Photographs were even taken of African American middle class working conditions and places of worship to show just how far African Americans had progressed since their days of servitude.

Aside from highlighting social advancement, these pictures also demeaned the disparaging notion that African Americans were less than human. In fact, the pictures proved to a European audience that African Americans were as equally human as whites by showing African Americans participating in the same types of human experiences as whites. Not only were African Americans capable of engaging in these experiences, but they had the abilities to thrive in the same modern society as white Americans. Du Bois and Murray masterfully used pictures, literature, and patents to illustrate to the Europeans that the days where an African American did not even possess his or her own body were over; they now possessed the self-ownership and proper education to actively take part in a larger global community.

During the fair, the exhibit was practically snubbed by the other American exhibitionists, and the mainstream news outlets generally ignored it. It was even relegated to a location separate from the main United States exhibit. Though dismissed by the American exhibitionists, the Exhibition of American Negros was extremely popular amongst the patrons of the fair. Europeans gawked at the amazing images and were astonished at the oeuvre of literature displayed. Even some American patrons came away impressed. One anonymous American writer called it the “most authentic evidence of the literary output of the race” and another called it “a prophetic of what may be expected.” In sum, the project was a success. Du Bois and his team were able to take an exhibit that Du Bois referred to as “an honest straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss” and use it as a tool to quicken the march toward African American equality.

You can read an article related to African American Emancipation and the struggle for equality in the June 2014 issue of History is Now Magazine, our latest issue. You can even read it for free today if you take up a no-obligation trial now.

References

Anonymous. “Negro Authorship.” Publications of the Southern History Association, 4:4. 1900 (July): 295-296.

Anonymous. “The Negro in Literature.” Literary Digest, v.21, n.5 (August 4, 1900): 130

Du Bois, W.E. Burghardt. 1900. “The American Negro at Paris.” The American Monthly Review of Reviews, vol.XXII, no.5 (November): pp.575-577.

Du Bois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Penguin, 1989. Print.

Gnovis, Vol. 6 (Georgetown University’s journal of Communication, Culture, and Technology