Grigori Rasputin was an enigma of his age. He rose from obscurity to become a key friend of the Russian royal family. He was also said to have mystical powers. Following our previous article, we finish the story of a group who wanted to kill him – and Rasputin’s almost super-human powers to resist death.

We pick up the tale after Rasputin survived a cyanide attack…

Rasputin was observing a cabinet inlaid with ebony in the corner of the room when Yusopov returned with the gun concealed behind his back. He is reputed to have exclaimed, “Grigori Efimovich, you would do better to look at the crucifix and pray to it,” before shooting him in the chest. With his silk shirt stained with blood, Rasputin lay dead upon a bearskin rug. Yusopov informed the others of his success, but was ‘suddenly filled with a vague misgiving; an irresistible impulse forced me to go down to the basement.’ What followed next could be plucked straight from the pages of a horror story. According to Yusopov, ‘Rasputin leapt to his feet, foaming at the mouth. A wild roar echoed through the vaulted rooms, and his hands convulsively thrashed the air. He rushed at me, trying to get at my throat, and sank his fingers into my shoulder like steel claws. His eyes were bursting from their sockets, blood oozed from his lips. And all the time he called me by name, in a low raucous voice.’ Such claims should be taken with a pinch of salt, however: it is important to note that Yusopov was seeking to justify his actions by portraying Rasputin as a demonic monster from whom he had saved Russia.

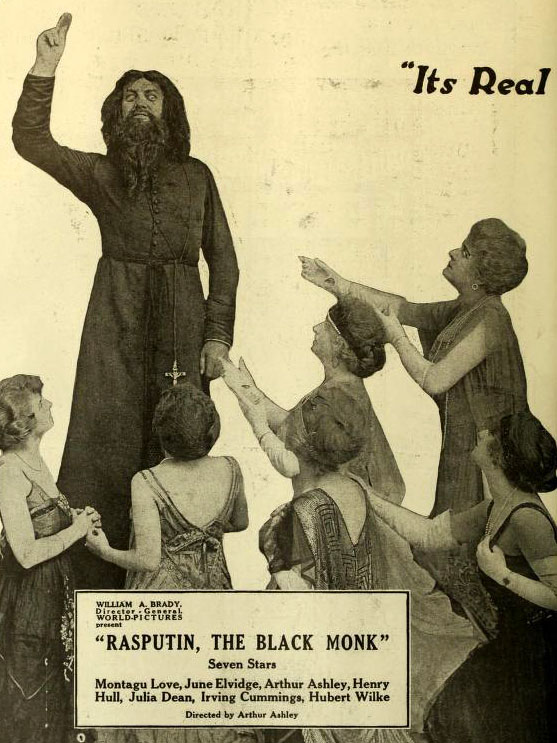

Mythical powers? A book “Rasputin, the black monk.”

As Rasputin attempted to escape through the garden, Yusopov called for assistance from Purishkevich. The latter seized a revolver and felled Rasputin with two shots. Together, they bound his body and drove to the Malaya Nevka River, where they cast it off a bridge into an ice-hole. Two days later, a frozen corpse was dredged up, and, to the amazement of onlookers, Rasputin’s arms were raised as though he had been struggling to escape from his bonds. Some press reports even suggest that a few people rushed to the site clutching pots and buckets, believing that the water surrounding this individual might instill in them a measure of his mystical power.

Whilst the murderers’ accounts are compelling, they are flawed and inaccurate, and do not stand up to close scrutiny. The autopsy carried out on the thawed corpse refutes many of Yusopov’s exaggerated statements. It revealed that Rasputin had been hit three times: once in the left side of his back, once in the left side of his chest, and once at close range in his forehead. The pathologists confirmed this final shot to be the cause of death, yet Purishkevich never mentioned firing a bullet into Rasputin’s head from such a short distance. The final contradiction of Yusopov’s testimony was the absence of poison in the body.

As if the historian’s role is not challenged enough by excavating the past for gems of truth amongst the rubble of legend, let us now introduce Lieutenant Oswald Rayner to the list of dramatis personae. There is considerable evidence that the British viewed the situation in Russia as increasingly precarious and unstable: a mercurial compound jeopardised by the oxygen of revolution. The ambassador at the time, Sir George Buchanan, gave voice to these concerns in a meeting with the Tsar himself, in which he implored him to make some concessions regarding the constitution. “If I were to see a friend walking through a wood on a dark night along a path which I knew ended in a precipice, would it not be my duty, sir, to warn him of his danger? And is it not equally my duty to warn Your Majesty of the abyss that lies ahead of you?”

Rayner was a British officer employed by the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) in St. Petersburg. He was also a contemporary of Felix Yusopov, for the two men had formed a close relationship when studying together at Oxford. The British were worried that Rasputin’s significant influence over the royal family would result in his directing them to withdraw troops from the war. This would have been catastrophic for the Allies. Russia’s conflict with Germany in the East provided a crucial buffer, as it meant that the Germans could not concentrate all their forces on one front.

Rayner visited the Yusopov residence on several occasions around the time of Rasputin’s death, leading some to suspect the SIS of instigating the assassination. Was it Rayner who shot Rasputin in the head with the precision of a trained killer? There were certainly persistent rumours that he had somehow been involved; even the Tsar and his family became wary of Buchanan and his supporters. The intelligence historian, Andrew Cook, uncovered an incriminatory message sent by a British intelligence officer in the aftermath of Rasputin’s death. If Rasputin is the ‘Dark Forces’ to which he refers, then this memo is most damning indeed: ‘Although matters here have not proceeded entirely to plan, our objective has clearly been achieved. Reaction to the demise of “Dark Forces” has been well-received by all… Rayner is attending to loose ends.’

Historians can dissect documents and posit theories, but, ultimately, the true events of that night will continue to elude them. Instead, they must sift through the pile of myths and reach their own conclusion. Should Yusopov’s account take precedence over others? Was the SIS complicit in the murder, or, indeed, can a different explanation altogether be justified? The most compelling aspect of Rasputin’s story is the aura of mystery surrounding his death: the truth has been swept away by time, with only a few fragments of the past remaining, half-glimpsed through the prism of the years.

By Julia Routledge

If you enjoyed this article, take a look at Julia’s recently published book on George Orwell. You can view the book here: Amazon US | Amazon UK

References

- Lost Splendour: The Amazing Memoirs of the Man Who Killed Rasputin – Felix Yusopov

- My Mission to Russia, and Other Diplomatic Memories – Sir George Buchanan

- How To Kill Rasputin: The Life and Death of Grigori Rasputin – Andrew Cook