We continue our story of Italian colonialism in Libya, following our previous article on the Italian invasion.

The 1912 peace treaty between Italy and the Ottoman Empire may have ceased the two state’s hostilities but the Libyans persisted in their guerilla-warfare struggle against their new Italian occupiers. This transfer of sovereignty meant little to the average Libyan, as one commentator later stated:

The legal transfer of sovereignty… seemed meaningless to Muslims, who fought the war not in the name of Ottoman sovereignty over Libya, but in the name of Islam.

From 1912-1915, Libyan resistance was strongest in the eastern province of Cyrenaica, where the organized Sanussi Order rallied tribesmen under the leadership of Ahmed al-Sharif, equipped with arms left by the Ottomans. Their Libyan counterparts in Tripolitania weren’t as effective, having failed to muster a sizeable Berber army. In the resulting power-vacuum, Fezzan (Libya’s south) was vulnerable to French occupation. Indeed, in 1913, a French army was already en route to occupy the regional capital of Ghat.

Once again, Italy had to respond to provocative French actions in North Africa and hurriedly arranged an expedition numbering thousands into the Fezzan in July 1913. Despite capturing several key towns and oases, the Italian supply lines were overstretched and vulnerable to attack by Libyan resistance fighters. The commanding colonel, Miani, knew he had as little hope of conquering Fezzan as the Roman general Balbus did over 2000 years earlier. The Sanussi tribesmen struck under Ahmed al-Sharif’s brother, in August 1913. Within weeks, the brief Italian occupation of Fezzan had ended and the tide began to turn in favor of the Libyans. The garrisons in the towns of Edri and Ubari were massacred and the fort of Sabha retaken. The Italians, numbering just one thousand, had to flee to French Algeria for protection.

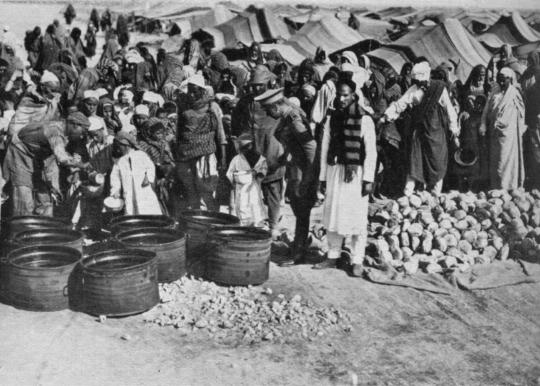

Image from the El Agheila concentration camp

After several skirmishes, the Sanussi-led fighters began to push towards the coastal city of Sirte in April 1915. The Italians counter-attacked with a force of 4,000 soldiers under colonel Miani, to be supported by 3,500 Libyan auxiliaries under the leadership of Ramadan al-Suwayhli of Misrata. Ramadan had initially fought and later collaborated with the Italians, who by now had assumed he was loyal towards them. On April 29, the two sides met at Qasr Bu Hadi (south of Sirte). Just as the battle started, Ramadan ordered his soldiers to open fire on his Italian comrades. Sources described the battle as a massacre, with only a handful of Italians (Miani included) escaping. The Libyans captured thousands of rifles and millions of rounds of ammunition, as well as artillery, and marched on to capture Misrata. The Italians panicked, with several garrisons abandoning their posts. On July 5, the Italians issued a general withdrawal order to the coastline, where they could be protected through Italian naval bombardments.

World War I and the British

Italy was already preoccupied with the outbreak of World War I, which resulted in much of the Italian force in Libya being recalled to the mainland. With the withdrawal of active Italian units, factional disputes began to arise amongst the tribal allies of Libya. Several ‘regional governments’ were set up across newly liberated territories, each headed by militant leaders. For example, in 1915, Western Tripolitania was controlled by Suf al-Mahmudi, and Eastern Tripolitania and Misrata was controlled by Ramadan al-Suwayhli, while Khalifa al-Zawi controlled Fezzan until 1926. Even though these regional governments were short-lived, it highlighted the fractured nature of the Libyan fighters. This fracture arose due to socioeconomic differences and quarrels over revenue.

Aid would soon arrive to Italy in an unexpected form though – the United Kingdom. As nominal allies in WWI, an enemy of Italy was therefore the UK’s enemy. In 1915, a British army inflicted a heavy defeat on the Sanussi army in the Egyptian desert, a defeat that saw Ahmed al-Sharif surrender his title as Grand Master of the Sanussi Order to Muhammad al-Idris (who would later go on to be King Idris in 1952). In 1917, the British mediated an agreement between the Italians and Idris wherein the Italians acknowledged Idris’ control of Libya’s interior and also gave autonomy to Tripolitania’s numerous regional governments. Later that year, Idris (with the support of the British government) negotiated another agreement with the Italian government, which called for an end to all hostilities, the recognition of Italian and Sanussi zones in Cyrenaica, outlined security responsibilities of both parties, and called (ambiguously) for the disarming of the tribes.

Why would Italy make these concessions? After going through decades of peaceful penetration and years of war, why? The answer is simple. The Great War in Europe forced Italy’s hand; peace, or at least a ceasefire, would free up thousands of Italian soldiers to defend the Italian homeland. The ends justified the means and the Italians had to compromise with the Libyan nationalists, this did not leave the Italian government free from criticism for being “too impractical”. Italy passed statutes that gave limited self-governance to Tripolitania and Cyrenaica and elections for an ‘advisory parliament’. A more liberal approach to Libya was adopted. For now.

The first Arab Republic and the rise of Mussolini

In 1918, the Arabs of Tripolitania capitalized on Italy’s weakness and declared the independence of the Tripolitanian Republic (which is also the Arab World’s first republic) under the leadership of the Committee For Reform, based in Misrata and headed by Ramadan al-Suwayhli, the dominant figure in Eastern Tripolitania. Largely symbolic and seen by contemporaries as the “seed for an independent Libya”, the republic was very unsuccessful. Once again, tribal infighting prevented a united response against the Italians. The Tripolitanian Assembly failed to convene at all due to petty rivalries and the assembly was dissolved in 1923. In contrast, the Cyrenaican parliament of the same period met five times and was generally more effective than its counterpart. However, the establishment of political entities in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania was a significant attempt at establishing political unity between the two regions, although by the 1920s, Italy had other intentions.

August 1921 marked the arrival of the eleventh governor of Libya in 10 years, Giuseppe Volpi, to Tripoli amidst the raging wave of Fascism sweeping the Italian mainland. On October 28 1922, Benito Mussolini marched into Rome and began what would be a 21-year Fascist dictatorship of Italy. Mussolini, eager to gain domestic triumphs, set his eyes upon reconquering Libya. He authorized Volpi to conduct a Reconquista of Libya. Volpi arrived in a Libya where the Italians controlled nothing beyond the barbed-wire fences and where Libyan nationalists demanded even greater self-rule. By April 1922, Volpi amassed an army of 15,000 soldiers (20,000 by 1926) and made his intentions clear. The only way to rule Libya was direct rule from Rome. He summarized his policy as;

“Neither with the chiefs nor against the chiefs, but without the chiefs”

In early 1923, Volpi’s campaign began. What happened during and in the aftermath of the campaign was later described as textbook genocide by historians.

Supporting Italy’s soldiers were an armada of airplanes, artillery and even poison gas. Though Italy was a signatory of the 1925 Geneva Convention that banned chemical weapons in battle, Italian forces were recorded to have used poison gas as early as January 1928.

By the end of 1924, Tripolitania was subdued and the republic dissolved. It would take four more years before the Sanussi of Cyrenaica would surrender to the Italians. In 1929, the two regions and northern Fezzan were united into one entity, Libya, under the control of a military governor. Idris had fled to Egypt by then.

Fascist Italy’s Victory

Libyan authorities placed the casualty figure at 750,000. Large number of communities were uprooted and sent to concentration camps, where they were slaughtered. Contemporary sources describe the situation in the camps and major cities. Von Gotbery, a German visitor in Tripoli, stated:

“No army meted out such vile and inhumane treatment as the Italian army in Tripoli. General Kanaiva has shown contempt for every international law, regarding lives as worthless”

Knud Holmboe, a Danish Muslim, described a concentration camp he visited that was said to contain six to eight-thousand people:

“The children were in rags, half hungry, half starved…. The Bedouins…looked incredibly ragged…many of them seemed ill and wretched, limping along with crooked backs, or with arms or legs that were terribly deformed.”

In the spring of 1923, over 23,000 Libyan nomads were rounded up in concentration camps. The imprisoned Arabs would suffer from repeated armored charges, killing an average of 500 men, 30,000 sheep, and 2,300 camels.

By 1930, the rest of Fezzan was reconquered. By this time, General Graziani was in charge of Libya. He was praised in Italy as a national hero; in Cyrenaica he was called “Butcher Graziani”. The ‘credit’ should not be his alone though. Historian Geoff Simons argues that the Italian Colonial Ministry, the military governor, the Italian press, and the Italian Fascists all played their part in the genocide.

In March 1930, Graziani landed in Benghazi where he discovered that Libyan nationalists were still engaging in skirmishes, under the leadership of Omar al-Mukhtar. Omar himself was injured and Graziani believed he had a mere 600 guns at his disposal. Calling Omar a ‘poisoned organism that should be destroyed’, he believed that disposing of Omar al-Mukhtar would destroy the Libyan rebellion. Observers believed that Graziani had a personal vendetta against Omar but in fact, he was intent on destroying all Libyan resistance.

Graziani had no limits to his plans to destroy the Libyan resistance. He proposed bombing suspected rebel encampments with mustard-gas bombs. In June 1930, Graziani proposed the mass deportation of Libyans as a means of separating civilians from the guerilla fighters. The Italian general (and later Prime Minister) Pietro Badoglio wrote to Graziani and told him that the mass deportations of tribes were “a necessary measure”. In a letter, he went on to say:

“We must, above all, create a large and defined territorial gap between the rebels and subject population. I do not conceal from myself the significance and gravity of this action, which may well spell the ruin of the so-called subject population. But for now on the path has been traced out for us and we have to follow it to the end even if the entire population of Cyrenaica has to perish”

The end of the resistance

Graziani’s final move in Cyrenaica was the construction of a 200-mile long barbed wire fence along the Egyptian border in 1930. This was meant to restrict the movement of Omar al-Mukhtar’s guerilla forces into neutral Egypt. On September 11 1931, Omar’s group of 12 was intercepted by Italian forces after being spotted by an Italian airplane. Omar was captured while the rest were gunned down. On September 12, he was sent to Benghazi on board an Italian destroyer and was correctly identified by Italian officials. The Italian general Badoglio relished the moment. He wanted to put Omar on show-trial and execute him in a concentration camp. Graziani organized a trial and the general consensus amongst Italians was that Omar should be executed. After an extremely short court hearing, in which the prosecutor was very sarcastic and partisan, the death sentence was handed to Omar.

Omar Mokhtar arrested by Italian Fascists

At 9am on September 16 1931, Omar al-Mukhtar was hanged in front of 20,000 inmates in the Solouk concentration camp.

It took exactly 20 years to subdue Libya. The Italian Reconquista was brutal. Civilians and their livestock were deliberately bombed. Prisoners were thrown alive outside airplanes in mid-flight. There were reports of inmates being crushed to death by tanks. Thousands of suspected rebels were arrested and shot. Though no definitive casualty number is available (the Italian colonial archives are still restricted), two-thirds (110,000 people) of Cyrenaica’s population were interned into concentration camps, of which 40,000 perished. On January 24 1932, General Badoglio declared that the war was over. The colonization of Libya could begin.

By Droodkin

Droodkin owns the international history blog – click here to see the site.

And the next in the Libya series is here:

Fourth Shore – The Italian Colonization of Libya

PS – Why not join our mailing list to hear about more great articles like this? Click here!

References

Libya: From Colony to Revolution by Ronald Bruce St. John, pages 1930-1936 (I recommend a read if you would like a greater detail of the events above)

Libya and the West: From Independence to Lockerbie by Geoff Simons, pages 7-12