John Adams was one of the Founding Fathers of the USA. After US independence was achieved, he served in a number of positions, including as the US Minister to Britain, a crucial role at the time. Here, Steve Strathmann looks at how Adams fared while in London.

After the American Revolution and throughout the nineteenth century, Anglo-American relations saw many highs and lows. While the United Kingdom and the United States only went to war once during this period (War of 1812), tensions were always close to the surface. This situation made the position of United States Minister to the Court of St. James’ one of the most important in the US State Department. Among the many men who held this post (including five future presidents), three members of the Adams family served in London at points during or after times of war. John, his son John Quincy and his grandson Charles Francis all faced challenges during their terms, but each contributed to the slow but steady strengthening of bonds between the British and their former American colonies. This first of three articles will deal with the first American minister to London, John Adams.

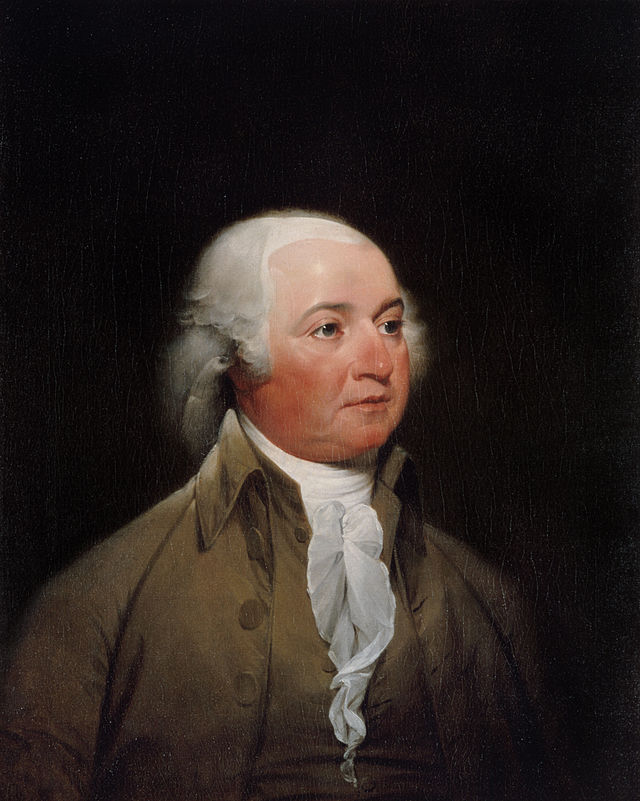

A portrait of John Adams, circa 1792. By John Trumbull.

Meeting George III

At the time of his appointment to London in 1785, John Adams had been in Europe for about three years. During that period, he had served as ambassador to the Netherlands (a post he would continue to hold while in England) and served on the committee that negotiated the Treaty of Paris, which ended the war with Britain.

He presented his credentials to King George III on June 1, 1785. In his speech to the king, Adams stated that he hoped that he could help restore the “good old nature and good old humor between people who… have the same language, a similar religion, and kindred blood.”

John Adams later reported that George III seemed very affected by the meeting. In his response, the king stated that he was the last person to agree to the breakup between Great Britain and the American colonies. On the other hand, since it was now fact he “would be the first to meet the friendship of the United States as an independent power.”

Public Reception of Minister Adams

The choice of Adams as the chief American representative in Britain was widely scorned by the London press. This was no surprise, given Adams’ roles in promoting American independence and negotiating the treaty which achieved that end. According to historian Joseph J. Ellis, the press reaction to Adams was “much like the Vatican would have greeted the appointment of Martin Luther”. Adams took the way that some people acted towards him during his term as showing guilt and shame, as opposed to anger. He wrote in his diary after one awkward party in March 1786: “They feel that they have behaved ill, and that I am sensible of it.”

John’s wife, Abigail, had joined him in Europe. She helped fortify him against the attacks, but also had to deal with slights of her own. For example, the wife of an MP once asked her, “But surely you prefer this country to America?” John Adams’ official relations with British authorities were more cordial than with the press and some of the public, but that didn’t necessarily show up in any kind of diplomatic results.

Diplomatic Standoff

John Adams’ primary goals while in London were to settle violations of the Treaty of Paris and arrange a trade agreement between the two nations. Among the violations, British troops continued to occupy posts along the Great Lakes. When this was brought up to Foreign Minister Lord Carmarthen, he countered that prewar debts owed by American farmers to British creditors had yet to be paid, also a treaty violation. This is one example of the stalemate on treaty issues that Adams was unable to break during his tenure.

Adams also made no progress on a trade agreement with the British. The trade balance was firmly in London’s favor at this time. They felt no need to make concessions on items such as opening their West Indies ports to American ships. Unfortunately for Adams, he had just as many problems dealing with his own government as with Lord Carmarthen and the British.

This was because of the rules set forth under the Articles of Confederation. Congress had no power over foreign trade, so it could not help in arranging any trade agreement with Great Britain. The military was so weak under this system that it could do nothing about British forces on the Great Lakes even if it wanted to. Congress also proved slow in providing instructions to its ambassadors. In fact, when Adams requested to be relieved of his European posts in order to return home on January 24, 1787, Congress didn’t approve his request until October 5. Due to the slow pace of communications across the Atlantic Ocean, Adams didn’t receive this news until mid-December, almost a year after sending his request.

Progress Elsewhere

Though John Adams may have struggled in his negotiations with the British, this period was not unproductive for him. He, along with Thomas Jefferson, did finalize deals with several other nations. Prussia signed the only trade agreement that the Americans were able to complete during Adams’ term on August 8, 1786. A treaty with Morocco was signed in early 1787, in which the United States agreed to pay for the protection of American shipping. They also secured additional loans for the United States from the Dutch.

John Adams also made his thoughts known back home over the future of the United States government. The weakness of the Confederation Congress had led many to call for changes to, or an entire replacement of, the Articles of Confederation. Adams’ contribution to this debate was A Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America, which he had published in London and shipped to America. In this book, Adams argued for a bicameral legislature (as opposed to the single Confederation Congress) and an executive branch empowered to carry out the laws and defend the nation. The book was well received in the States, and James Madison wrote that it would be “a powerful engine in forming the public opinion.”

Return to America

John Adams made so little headway during his three years in London that his post would remain vacant for the next four years. In his final meeting with George III, the king assured him that when the Americans met their treaty obligations, his government would as well. After Adams left London on March 30, 1788, the Westminster Evening Post reported that he “settled all his concerns with great honor; and whatever his political tenets may have been, he was much respected and esteemed in this country.”

No one knew at the time, but this would not be the last time an Adams would represent his nation in the Court of St. James. In 1815, following another Anglo-American war, John Quincy Adams would assume his father’s former position in the diplomatic corps.

Read more about John Adams and why Independence Day may not actually be on July 4. Click here now!

References

Butterfield, L.H. et al., eds. Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, Vol. 3. Cambridge, MA: Belkamp Press of Harvard University Press, 1962.

Ellis, Joseph J. First Family: Abigail Adams & John. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

Holton, Woody. Abigail Adams. New York: Free Press, 2009.

Madison, James. Volume 1 of Letters and Other Writings of James Madison. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott & Company, 1865. Accessed June 21, 2014. http://books.google.com/.

McCullough, David. John Adams. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.

United States Department of State. “The United Kingdom-Countries-Office of the Historian.” http://history.state.gov/countries/united-kingdom. Accessed June 15, 2014.