Cigarette advertisements were banned in many countries some time ago; however, this was not always the case. Prior to World War Two, cigarettes were believed to be good for you and advertising was allowed. And, as women’s power in society grew in the early twentieth century, so did their propensity to smoke cigarettes. Here, Rowena Hartley investigates how cigarette companies got women hooked on cigarettes through advertising…

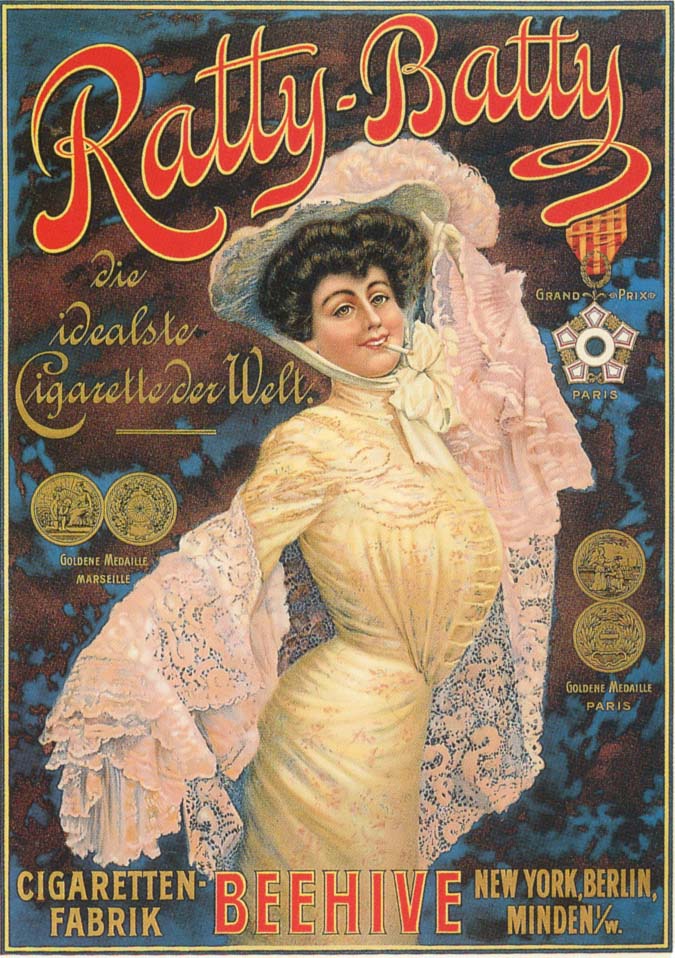

A German cigarette advertisement, circa 1910.

Cigarettes and Mass Production

Nowadays the glorification of cigarettes is the domain of old movies and television shows, and we are far more likely to see adverts graphically detailing how they can harm us. Despite this, cigarettes have remained highly popular in almost every rank of society for over a hundred years. And yet, to begin with, they were a symbol of wealth. The very first cigarettes were hand rolled, which took precision and time, so could only be purchased by those who had plenty of disposable income. However, at the Paris Exhibition in 1883 American inventor James T. Bonsack presented a working model of his cigarette-rolling machine which could make 300 cigarettes a minute. The Wills brothers in England quickly snapped up this cigarette machine, but it was not long before a similar device called the Bohl machine was invented allowing other cigarette companies to compete in this market. Suddenly the market was flooded and not just with Wills but with Players & Sons, Lambert & Butler, and De Reszke cigarettes amongst others. By World War One cigarettes were the most popular form of tobacco and were being sold for the very accessible price of 5 cigarettes for a penny.

The flooding of the tobacco market meant that, to begin with, cigarette companies spent vast amounts of money advertising their product to secure customers – only to find that their competitors were doing exactly the same thing and thus frequently cancelling out all of their efforts (this had the odd effect that when cigarette adverts were banned it actually meant that the cigarette companies had more profits as they were still selling the same amount of cigarettes). What this has to do with the early days of cigarette advertising is that on the whole smokers make very loyal customers, so once they started on one brand they were likely to continue to buy that same brand. Therefore, cigarette companies, soon after discovering the glory of untapped customers, were unable to show any further growth in the market or any proof that the advertising was working. In search of greater profits the cigarette companies decided to look to a previously ignored market: women.

Cigarettes, Women and sexual promiscuity

To begin with, women were not heavily targeted by cigarette advertisements, as cigarettes were a luxury item; their availability was highly restricted even amongst working men, never mind non-working women. Therefore it was generally only through men that women could access cigarettes and many women experimented with smoking by borrowing their husband’s pack. In itself this did not have any negative connotations but in the late nineteenth century unmarried men and women were closely observed and any behavior deemed inappropriate was quick to be frowned upon. So a man and a woman would have had to stand tantalizingly close to light a cigarette, and this was soon seen as provocative behavior, even foreplay. The image of a man and woman smoking in bed together still has strong and very obvious connotations about their earlier activities, although these implications were not just limited to amateurs. There was soon a strong association between cigarettes and prostitutes as they would often accept cigarettes from customers and then smoke them in the street whilst awaiting further business. This image was furthered by adverts warning men about the dangers of overly friendly women. Adverts of the time show that the combination of a cigarette and red lipstick apparently fits perfectly with “syphilis-gonorrhea”. The other (slightly less insulting) image of female smokers was that of the “New Woman” who was the subject of derision for the newspapers as she smoked heavily, drank heavily, wore men’s clothing, and neglected her household duties.

Despite the stigma, and in some cases because of it, cigarettes began to steadily grow in popularity so that by the end of the 1940s in the USA 33% of women smoked compared 50% of men, and in Britain 40% of women smoked compared to 60% of men. The increase in female smokers partially mirrored the growth of the market in general as cigarettes were becoming increasingly easy to purchase. The early twentieth century also saw a rise in working women, so it was more common for women to buy their own cigarettes and smoke them in and around their workplace. However, during the growth of female smokers from the 1880s to the 1940s, consumption was not just a grass roots movement. It was one heavily manipulated and encouraged by the tobacco industry.

Opening the Market

When tobacco companies started to market to women, they were important commodities. Most men were either non-smokers or dedicated to a particular brand; whereas women had less loyalty as they had not been directly targeted by cigarette companies to anywhere near the same extent. Therefore, there was a high chance that the company which encouraged women to smoke would also be the company who cornered most of that market. It is true that some women were already smoking before cigarette companies began to target them as consumers, but the majority did it at home and in secret in order to avoid the stereotypes associated with female smokers. This was not good for a tobacco company as it meant that there was less word of mouth advertising and fewer cigarettes consumed as women were limited in where they felt comfortable smoking them. This particular issue gave rise to Edward Bernays’ 1929 advertising campaign for Lucky Strike, where in the Easter Day Parade in Manhattan suffragettes would smoke “Torches of Freedom” to show their defiance against male dominance. The marching smokers did cause quite a stir not least in the sales of Lucky Strike, which sold 40 billion cigarettes in 1930 compared to 14 billion just five years earlier. After such shock tactics it became more common to see women smoking in public.

Although women smoking in public were becoming more acceptable there was still a major hurdle to overcome, which was that the cigarettes themselves were still made to suit men’s tastes. In the early days some cigarette companies, such as Wills, were hesitant to create a brand purely aimed at women, but it soon became clear that such attention could mean the difference between attracting and losing customers. In Britain the survey group Mass Observation found that women had to train themselves to like cigarettes or as one described it give “at least an appearance of enjoyment”. While that is also true of men, women were more likely to admit it. This meant that cigarette companies actually began to change the cigarettes themselves in order to have brands which appealed directly and almost exclusively to women. The number of Egyptian and Turkish blend cigarettes increased as their taste was milder and they also looked better in cigarette holders. In a more blatant stunt, Slims created a thinner cigarette in order to make it, and the hand attached to it, appear more elegant. Cigarette companies also began to manufacture jeweled accessories to further encourage smoking as well as brand loyalty. These were often in the form of cigarette cases with mirrors on the inside that made the product look more feminine but also subconsciously made the smoker relate checking her appearance to reaching for a cigarette. So society was open to female smokers, the manufacturers were directly targeting women, and cigarette companies were selling cigarette accessories. The final piece in the jigsaw was advertising.

Advertising Cigarettes to Women

Advertisers have found that the best way to sell their products is by having one clear selling point that they focus upon to attract the consumers’ attention. Once a brand is more established they can begin to have more ambiguous adverts, or introduce a new selling point to remind consumers of their product, such as offering a toy meerkat in order to compare insurance companies. However, in the early days of selling women cigarettes, most of the tobacco companies tended to focus on two main areas: health and style.

It was not until the 1950s that cigarettes were directly linked to throat and lung disease, so to begin with there were many adverts that recommended cigarettes on health grounds. Some cigarettes were even advertised on the basis that they helped alleviate sore throats. And even when this was proved false Lucky Strike slightly altered their advertisements to say that physicians agreed the cigarettes were “less irritating because it’s toasted”; this managed to keep the attraction without making any suable claims. The other health claims at least had an element of truth in them as cigarettes also advertised their ability to relieve stress and encourage weight loss. The adverts relating to health benefits were aimed at both men and women, but stress and slimming claims were more commonly aimed at women rather than men. One of the original claims made for encouraging women to smoke was that women were of a more nervous disposition and so would need the calming influence of cigarettes to help control their anxious tendencies. Similarly after many years of corset advertisements it was not a great leap to point out the slimming effects of cigarettes; again Lucky Strike was the forerunner of this phenomenon with their “reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet”. Even so, although health advertisement continues to be a popular selling point, the majority of cigarette brands focused on far more fashionable ways of selling cigarettes.

A Lucky Strike advert from the 1930s showing the supposed health benefits of smoking. Source: tobacco.stanford.edu, available here.

Red Lips

It is a noted phenomenon in fashion that what originally might be seen as scandalous soon becomes another fashion item. Just as miniskirts and saggy jeans first shocked and provoked reaction, cigarettes soon went from a scandal to a fashion statement. Smoking is still a highly social activity and many smokers started due to their belief that it made them look sophisticated, an idea encouraged by film and television, as from the 1930s onwards almost every actor and actress seemed glued to a cigarette for most of the programs’ running time. For actresses such as Audrey Hepburn the cigarette holder became a vital part of her look and one that she is rarely seen without. Similarly, some actresses actually advertised for tobacco companies, for example Claudette Colbert (It Happened One Night)for Chesterfields and Barbara Stanwyck (Double Indemnity) for L&M Filters. Other tobacco companies bypassed the need to use actresses’ popularity to sell their products by creating highly stylized adverts such as Will’s Gold Flake which merely hinted at the sophistication cigarettes could bestow. Companies such as Slims and De Reszke adapted the product itself to entirely focus the product on women. Slims thinned their cigarettes and De Reszke began a “Red Tips for Red Lips” campaign in the 1930s where they cultured the end of the cigarette so that any lipstick marks would not be visible. However, despite the growth in the market, De Reszke’s Red Tips advert was one of the first cigarette adverts that directed itself solely at the female market.

In conclusion, although many of the adverts mentioned here were used to appeal to both men and women, in a matter of years women went from being an ignored market to making up almost half of consumers, a change which was in a large part down to the power of advertising. But, as with men, once female smokers were hooked and their loyalties claimed by a specific brand then it was back to the drawing board for the advertisers as they tried to find a new market to appeal to.

Did you find this article fascinating? If so, tell the world! Tweet about it, like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below!

References

- Matthew Hilton, Smoking in British Popular Culture 1800-2000: Perfect Pleasures, (Manchester University Press, 2000); https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=UjM8t6Ul73YC&dq=smoking+in+popular+culture&source=gbs_navlinks_s (Especially Chapter Four: ‘Player’s Please: The Cigarette and the Mass Market).

- Wills, B.W.E. Alford, WD & HO Wills and the Development of the UK Tobacco Industry, 1786-1965 (Methuen, 1973).

- Wendy Christensen, ‘Torches of Freedom: Women and Smoking Propaganda’, The Society Pages, February 27 2012, http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2012/02/27/torches-of-freedom-women-and-smoking-propaganda/

- Penny Tinkler, ‘”Red tips for hot lips”: advertising cigarettes for young women in Britain, 1920-70’, Women’s History Review, 10:2 (2001) http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09612020100200289