In this article, Robert Walshwrites about the history of the last meal for those condemned to death. He considers its Christian roots and looks at how it has been carried out in different states. Finally, we look at some of the more unusual last meal requests.

Study media reports of executions, recent or decades-old, and you’ll probably find mention of the prisoner’s last meal. Most prisoners spend their entire sentences eating whatever the prison kitchen provides and have no choice. Condemned inmates are traditionally allowed to choose their final meal though. Before British reporters were barred from witnessing hangings in the early twentieth century their reports usually mentioned whether a prisoner enjoyed their final breakfast. Today, American reporters often mention what prisoners have for their last meal, although prison authorities often call it a ‘special meal’, deferring to the prisoner’s feelings about their upcoming death.

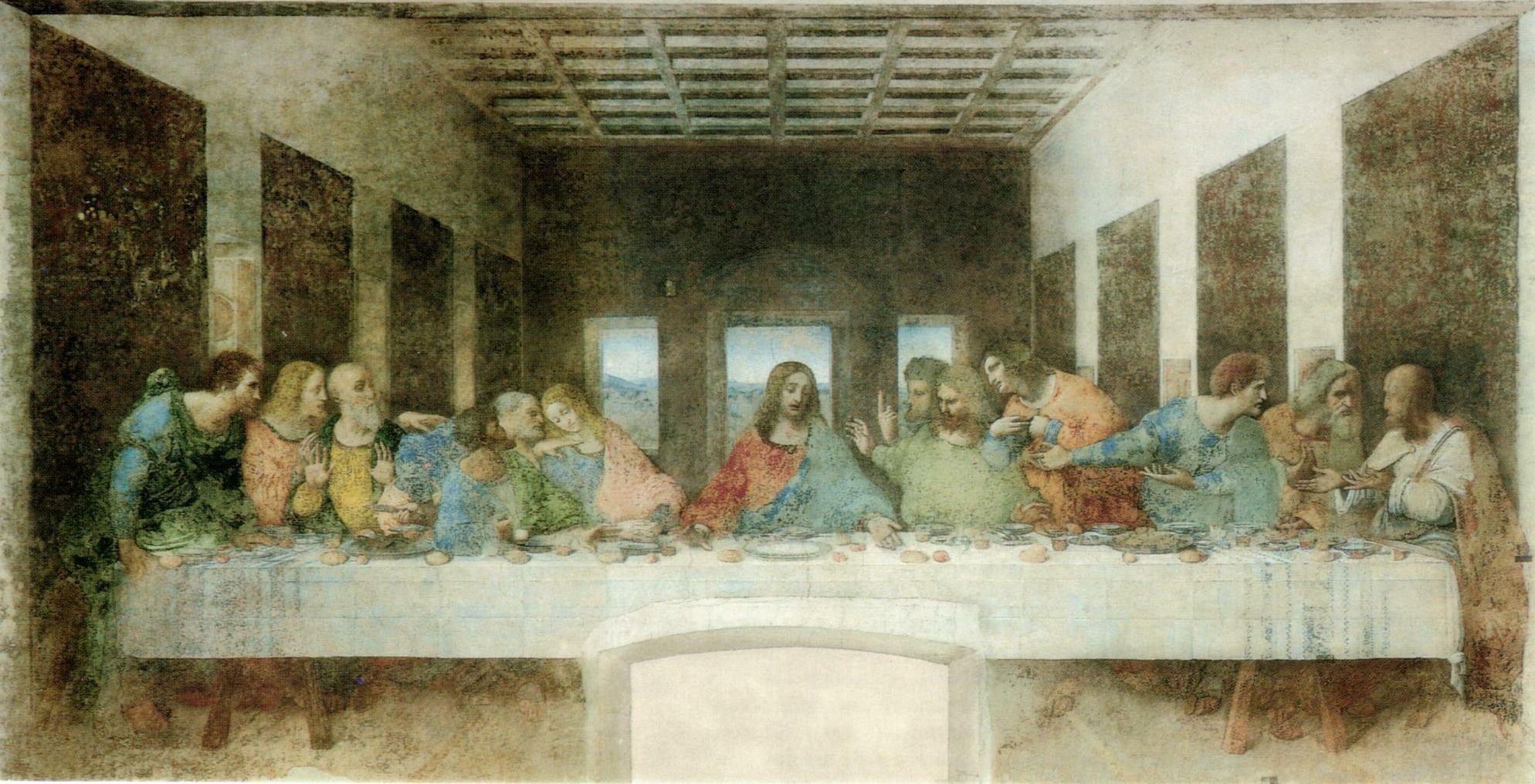

The Last Supper. Leonardo da Vinci. Late fifteenth century.

The last meal is usually a tradition, not a rule. No law automatically entitles prisoners to anything other than standard prison meals so it’s a privilege, not a right. It’s also far more significant than being merely a kind gesture. It’s an important part of the execution ritual and has been for centuries. Barring last-minute legal action a prisoner’s last meal is usually their last chance to control anything that happens in their final hours. Modern executions are usually conducted according to strict timetables and rigid rules with minimal deviation there from. In the US, a prisoner might wait over twenty years between sentencing and execution so their last freedom of choice can be very important to them.

RELIGIOUS SIGNIFICANCE

Execution is a grim ritual. The last meal is a part of that ritual and a ritual in itself. In medieval Europe it had religious significance dating back to when religion played a far greater role in daily life than it does today. A mental image of Christ’s Last Supper is often referenced as a parallel to a modern-day convict choosing their final menu. It also symbolizes a prisoner making peace with their executioners, breaking bread with them in the same way that Christ invited Judas Iscariot to the Last Supper. In modern-day Louisiana, a strongly-religious Southern state, Warden Burl Cain routinely invites condemned prisoners to eat their last meal with him and invited guests, offering the condemned Christian fellowship. Cain still supervises the execution, but he extends the invitation regardless. Naturally, the inmate isn’t obliged to accept.

Religion aside, superstition once played its part. In medieval Europe many believed that well-fed prisoners could be executed without fear of their returning as ghosts. The quality of the final meal was also believed to influence the likelihood of their doing so. If the food and drink were of the best quality it was believed that prisoners would be less likely to haunt their executioners. If the meals were poor, many believed prisoners would return as malevolent spirits bent on tormenting those involved in their deaths.

THE MEAL IN DIFFERENT STATES AND TIMES

What prisoners are permitted varies according to their location. In Texas, the last meal was introduced in 1924, the same year that Texas replaced the gallows with the electric chair and the State took over executions from individual counties. With one single Death Row located at Huntsville, the State of Texas centralized and standardized custody of condemned inmates which included granting them a last meal. Today, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice no longer allows last meals. Condemned inmates get the standard meal before execution. Other US States have widely-differing policies. Florida is comparatively generous, allowing a budget of $40. Oklahoma budgets only $15.

New York performed its last execution in 1963 (the state abolished capital punishment in the early 1970s) but was especially generous to its condemned. An inmate at Sing Sing Prison’s notorious ‘Death House’ could order both a last dinner and last supper. For example, murderer Henry Flakes was executed on May 19, 1960; his dinner consisted of barbecue chicken with sauce, French fries, salad, bread rolls, butter, strawberry shortcake with whipped cream, 4 packs of cigarettes, coffee, milk and sugar. Supper was equally generous: lobster, salad, butter and bread rolls, ice cream, a box of chocolate candy, four cigars, two glasses of cola, coffee, milk and sugar. Unlike many prisons today, Sing Sing’s condemned could include tobacco products like snuff, cigars, chewing tobacco and cigarettes. In 1930s Indiana, the State Prison at Michigan City was equally generous with last meal requests. Like Burl Cain today, on May 31, 1938 Deputy Warden Lorenz Schmuhl dined with murderer John Dee Smith at sundown and electrocuted him just after midnight.

Prisoners have often been offered alcohol just before execution, while prisoners facing firing squads have long been offered the traditional last cigarette. Both are partly a compassionate gesture, but also calm an inmate’s nerves in their final moments and make them more co-operative. In 1925 Patrick Murphy was executed at Sing Sing having pleaded with Warden Lewis Lawes for one final drink. In 1925 Prohibition was in force throughout the US so whiskey was forbidden for every citizen, incarcerated or otherwise. Lawes, a firm opponent of capital punishment and well-known to enjoy a pre-dinner Scotch throughout Prohibition, made a compassionate-yet-illegal decision. He broke both prison rules and Federal law, slipping Murphy a small bottle of bourbon an hour before his execution. Murphy took the bottle, looked at Lawes (who loathed executions) and died having returned the bottle to Lawes saying, “You look like you need it more than I do, Warden.”

British hangman John Ellis often recommended prisoners were offered a cup of brandy minutes before their execution. At California’s San Quentin Prison inmates were once allowed a little whiskey immediately before they entered the gas chamber. Nowadays American prisons allow no alcohol of any kind and, unlike 1960s New York, few prisons allow tobacco products as part of a prisoner’s final meal. When the state of Utah used the firing squad, prisoners were allowed a last cigarette but were escorted into the exercise yard to smoke it. Under Utah state law, smoking indoors in public buildings (including prisons) is forbidden because it’s a health hazard.

MORE UNUSUAL RITUALS

There are other lesser-known rituals associated with the last meal. Between 1924 and 1964 Texas electrocuted 361 inmates at Huntsville. As part of their last meal Texan inmates often ordered as many portions of dessert as there were condemned inmates. If a prisoner wanted ice cream and there were five other condemned inmates on Death Row, then the prisoner would ask for six portions of ice cream so that no condemned inmate endured an execution night without a parting gift to raise their spirits. In New York, a number of Sing Sing’s condemned either shared their last meal with another inmate (as Francis ‘Two Gun’ Crowley shared his with John Resko in 1931) or split their meal with all the other condemned (as did Raymond Fernandez, hours before his execution in 1951). Like the last meal itself, sharing food was a tradition rather than a right, but it often kept inmates more settled when one of them was about to die.

It’s not unusual for a prisoner’s final choice to reveal something about them. Some decline a last meal to demonstrate contempt for prison authorities or simply because fear has left them unable to face food. Others opt for old favorites, food they probably haven’t had since their arrest, perhaps as a consolation and reminder of happier times. Some order huge meals, some order small ones, some order food they’ve never tried before out of curiosity. A few inmates make choices that seem bizarre to others, but make sense to them such as Victor Feguer, hanged in 1963. Feguer requested a single olive, asking that the olive pit be placed in his shirt pocket before he was buried. A strange request unless you know an olive pit is a symbol of rebirth. New York’s last execution was of Eddie Lee Mays on August 15, 1963. Mays wanted no food or drink, only a packet of cigarettes and a box of matches. Matches were forbidden for condemned inmates so Mays received his cigarettes, but had to ask guards to light them for him. At San Quentin, one Jewish inmate ordered an elaborate kosher meal then requested his first ham sandwich. San Quentin inmate Wilson De la Roi turned his final meal into a joke. When asked for his choice he requested a packet of indigestion tablets. Asked why, he chuckled, remarking that he might have gas on his stomach.

All in all, the last meal is many things to many people. To some it’s a kind gesture that should be retained as a final compassionate act. To others it’s an unnecessary offer that the prisoners don’t deserve. To prisoners themselves it can be a gesture of defiance, a chance for one final joke, a last chance to try something new, something to look forward to as the clock ticks down or simply not worth bothering with. It’s certainly far more than simply ordering from a menu.

You can find out more about the death penalty in our podcast on prisoner’s final words. Click here to listen.

Finally, if you found the article interesting, tell others. Tweet about it, like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below.

References

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-15040658

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/08/29/comfort-foods-last-meal_n_1839009.html

http://murderpedia.org/male.M/m1/martin-leslie-dale.htm

http://www.kevinroderick.com/gas.html

http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/11/06/a-man-who-knew-about-the-electric-chair/

Condemned: Inside the Sing Sing Death House, Scott Christianson, NYU Press, 2001, Page 137.

Ibid, Page 166.

Murder One: They Went To The Death Chamber, Mike James, True Crime Library, 1999, Pages 3-16.

Have a Seat, Please, Don Reid, Texas Review Press, 2001, Pages 1-16.

Dead Man Walking, Sister Helen Prejean, Harper-Collins, 1996, Pages 110-112.

Diary Of A Hangman, John Ellis, True Crime Library, 1996, Page 21.

Death Row Chaplain, Byron Eshelman, Signet Books, 1972, Pages 30-31.